کاسینی، یکی از فضاپیکاهای ناسا توانسد در طی انجام ماموریت خود اقدام به جمع آوری 36 ذره از غبارهایی که در فضای بین ستارگان خارج از منظومه شمسی وجود داشتند را جمع آوری نماید

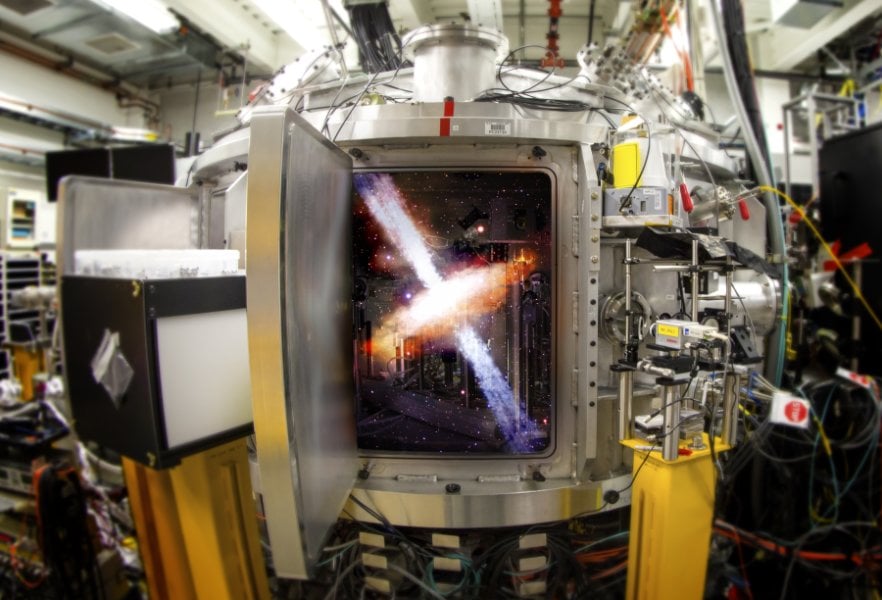

Since 2004, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has been orbiting Saturn to study the giant planet’s moons and rings using an array of complex instruments. One of these is a dust analyser, designed to scoop up particles ejected from a jet errupting from the surface of one of Saturn's moons, Enceladus.

While this is all pretty standard stuff for a spacecraft to do, NASA has just announced something a bit crazier: the craft has picked up 36 grains of interstellar dust that came from somewhere outside our Solar System. Oh, and the particles were moving at roughly 45,000 miles per hour (72,000 k/h), which is fast enough for them to pretty much ignore the Sun’s gravitational pull.

According to the team, this isn’t the first time some interstellar dust has been found floating around in the Solar System. Back in the 1990s, the joint ESA/NASA Ulysses mission found evidence of alien dust that researchers were able to trace back to an interstellar cloud.

Based on this previous find, the Cassini team knew where to look for dust particles as they flew by Saturn. As ESA researcher Nicolas Altobelli explains:

"From that discovery, we always hoped we would be able to detect these interstellar interlopers at Saturn with Cassini. We knew that if we looked in the right direction, we should find them. Indeed, on average, we have captured a few of these dust grains per year, travelling at high speed and on a specific path quite different from that of the usual icy grains we collect around Saturn."

This time around, the astronomers could use Cassini to analyse the particles right there in space to find out what they’re made of. Turns out, the grains consist of 'rock-forming elements' - notably magnesium, silicon, iron, and calcium - that were left over from the death of a distant star.

But the most surprising part of the discovery is the fact that the dust particles all share a similar chemical makeup, which is unique compared to other dust particles found on meteorites.

How this happened is still under investigation, but the team suspects that the grains formed from a dying star that condensed them with every shock wave. This means that the grains were likely destroyed and reformed multiple times making them more uniform every time.

The Cassini team is hopeful that the spacecraft will continue to collect interstellar dust samples that can further our understanding of the Universe abroad. We can't wait.

The research was recently published in Science.